Amobichukwu Amanambu

Pronouns: he/him

University of Florida

Adviser: Dr. Joann Mossa

Focus Area:

Research Statement:

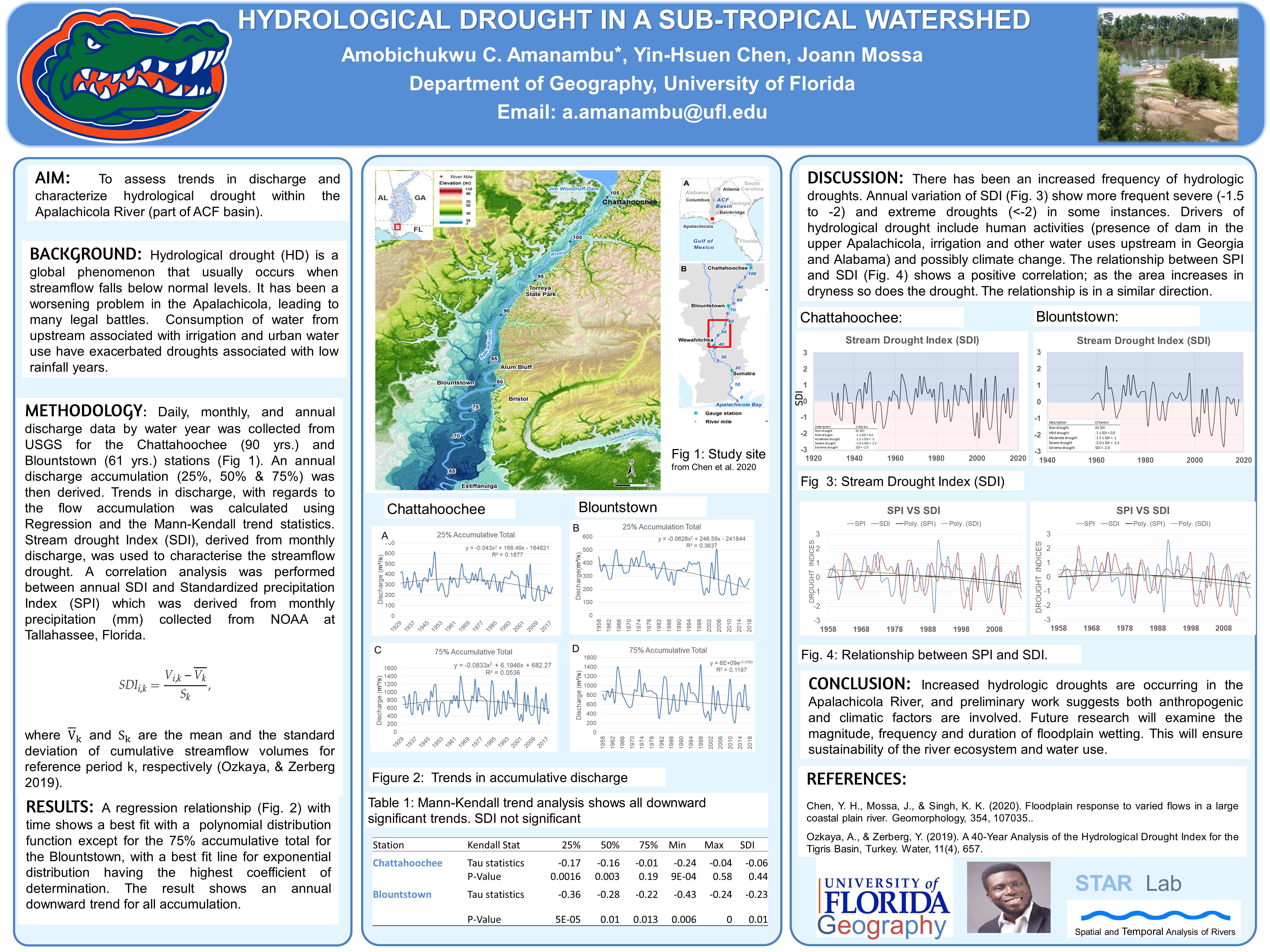

My interest in studying the Apalachicola watershed is to assess how physical and anthropogenic factors affect the drying (drought) and wetting (floods) of the river given the legal battle between Alabama, Georgia and Florida on water resources use in the ACF basin. Specifically, my overarching research question will be focused on how the construction of the 1954 dam—in the upper part (Chattahoochee) of the Apalachicola river basin—has impacted floodplain inundation and exacerbated hydrological drought as well as the river morphology. I will further examine the role of dredging in influencing inundation and drought while mapping the extent of dredging in the river using an unmanned aerial vehicle (UAV). This research is fundamental since rivers and their floodplain provide essential benefits to ecosystems and society. The study is expected to advance an analytical framework with the result that is useful for policy formulation.

Who is he?

Amobichukwu Amanambu is first generation student in his third year as a PhD student in the Geography Department. He is a Hydrogeomorphologist who grew up in Lagos, Nigeria.

How did he get here?

Amobi was born in Borno state in northern Nigeria. His parents felt that it was important that he and his siblings learn to speak Igbo, so he lived in eastern Nigeria for a few years, before moving to Lagos, Nigeria’s largest city, where his mom works as a caterer and his dad was a trader in Honda parts.

The Amanambu family spoke Igbo at home, but Amobi and his 6 siblings learned English at school. When he wasn’t studying, Amobi would play street football against teams of kids from the neighboring streets.

Amobi didn’t plan on becoming a geographer, but in secondary school (high school) he stood out as a top geography student, where he earned the nickname ‘map me no map’ meaning ‘his head is the map of the world’. On the strength of his geography test scores, Amobi enrolled in the Bachelor of Science in Geography program at the University of Ibadan.

While living on campus in Ibadan, there was a general strike of instructors and staff at universities across Nigeria. In an effort to keep the youth busy, the Nigerian government held the National Orientation Agency Essay contest. Among thousands of student submissions, Amobi’s entry What Nigeria Means To Me took 27th place overall in the nation and 3rd place in Oyo state. During the strike, Amobi also started a local news blog with a friend, which they later sold.

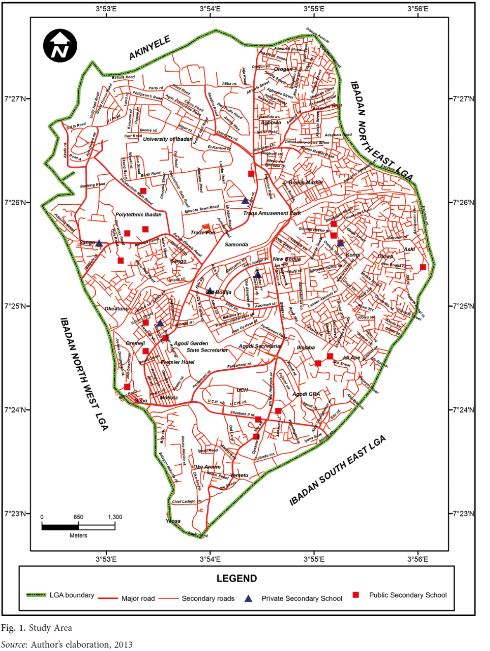

When courses resumed, Amobi dove into field work investigating water sanitation and hygiene in secondary schools. Using distance decay and location theory, he found that the further away that toilet facilities are from a water source, the more the sanitation decays. He published his findings with his undergraduate adviser Dr. Christiana Egbinola as Water supply, sanitation and hygiene education in secondary schools in Ibadan, Nigeria in the Bulletin of Geography, Socio-economic Series. At the university Amobi became interested in politics and debates, “I realized that if you are privileged to have power, you should use it to affect people who don’t. If you have the opportunity to be a policy maker, you should.”

Upon completing his B.Sc., Amobi joined the National Youth Service Corps (NYSC) for a year – a requirement for many graduate programs in Nigeria. The NYSC sent Amobi to Bauchi, Nigeria, where he taught agriculture, geography, and English language at the Jagun Women Secondary School. All of his students were married women – many of whom had been married as young as thirteen years old and had received little education.

Bulletin of Geography. Physical Geography Series

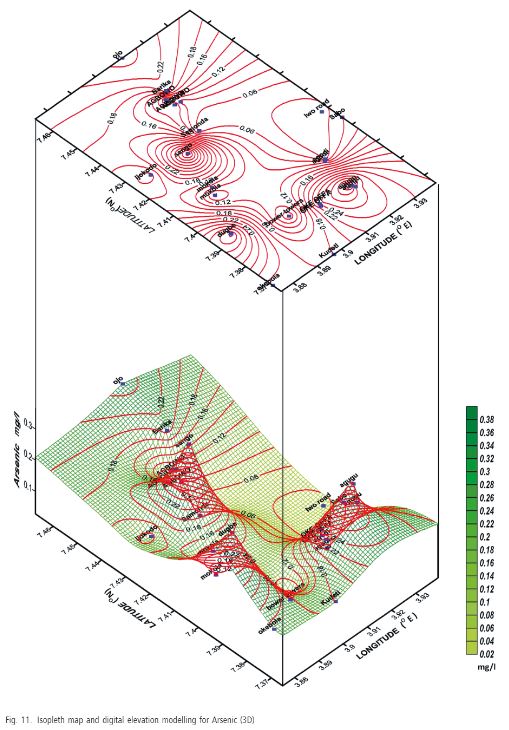

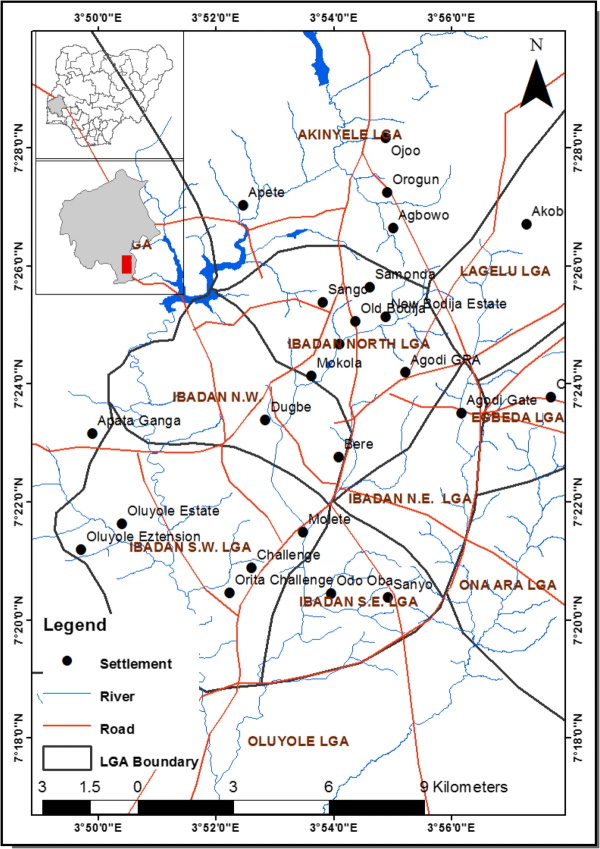

After a year in Bauchi, Amobi returned to the University of Ibadan, where he pursued a Master of Science in Geography. Amobi continued to be interested in water quality and public health questions, but pivoted to geogenic causes – water contamination from the rocks that ground water passes through. With a handheld unit to assess water temperature and pH, Amobi returned to the field to collect water samples around the Ibadan North water supply. The University of Ibadan Agronomy Lab performed analysis on Amobi’s samples, revealing that the rocks were indeed contaminating the water supply for a substantial portion of Ibadan. Amobi published his findings in Geogenic contamination of groundwater in shallow aquifers in Ibadan, south-west Nigeria, Geogenic Contamination: Hydrogeochemical processes and relationships in Shallow Aquifers of Ibadan, South-West Nigeria, and Groundwater contamination in Ibadan, South-West Nigeria.

After completing his Master of Science, Amobi started two new simultaneous courses of further study – he moved to the Chinese Academy of Sciences Xinjiang Ecology And Geography Institute for graduate studies and research and he started an M.Sc. in Water and Environmental Management at Loughborough University, United Kingdom as a virtual student through the Commonwealth Scholarship program. He takes one class at Loughborough University each semester and will complete his second M.Sc. in 2021.

While pursuing these new research opportunities, Amobi continued his interest in politics and civil engagement. “Although it’s painful to be living abroad and not be able to be involved,” Amobi felt it was important to give a voice to marginalized people back home, so he and some friends started Citizen NG a publishing platform where a community of citizens can publish stories, news, and art from an African perspective, without editorial gatekeepers or fear of censorship. They have made it particularly welcome to women and members of the LGBTQ community in Nigeria.

Amobi’s research had focused on ground water quality issues, but while at the Chinese Academy of Sciences he read Dr. Joann Mossa’s paper Anthropogenic landforms and sediments from dredging and disposing sand along the Apalachicola River and its floodplain. He and realized that he could blend his existing groundwaterground water knowledge with Dr. Mossa’s surface water research to develop a more complicated understanding of fluvial geomorphology in Nigeria.

What’s he been doing at UF?

When Amobi arrived at UF in 2018, he hit the ground running. He started by taking courses like GEO6938 Geospatial Modeling and GEO4281/GEO6282 River Forms & Processes. He’s appreciated the opportunity to learn the basic methods of being a fluvial geomorphologist. Amobi says, “if you don’t know the basic tools and techniques in your discipline, you can’t assess it – If you don’t know your history, you don’t know where you’re going.”

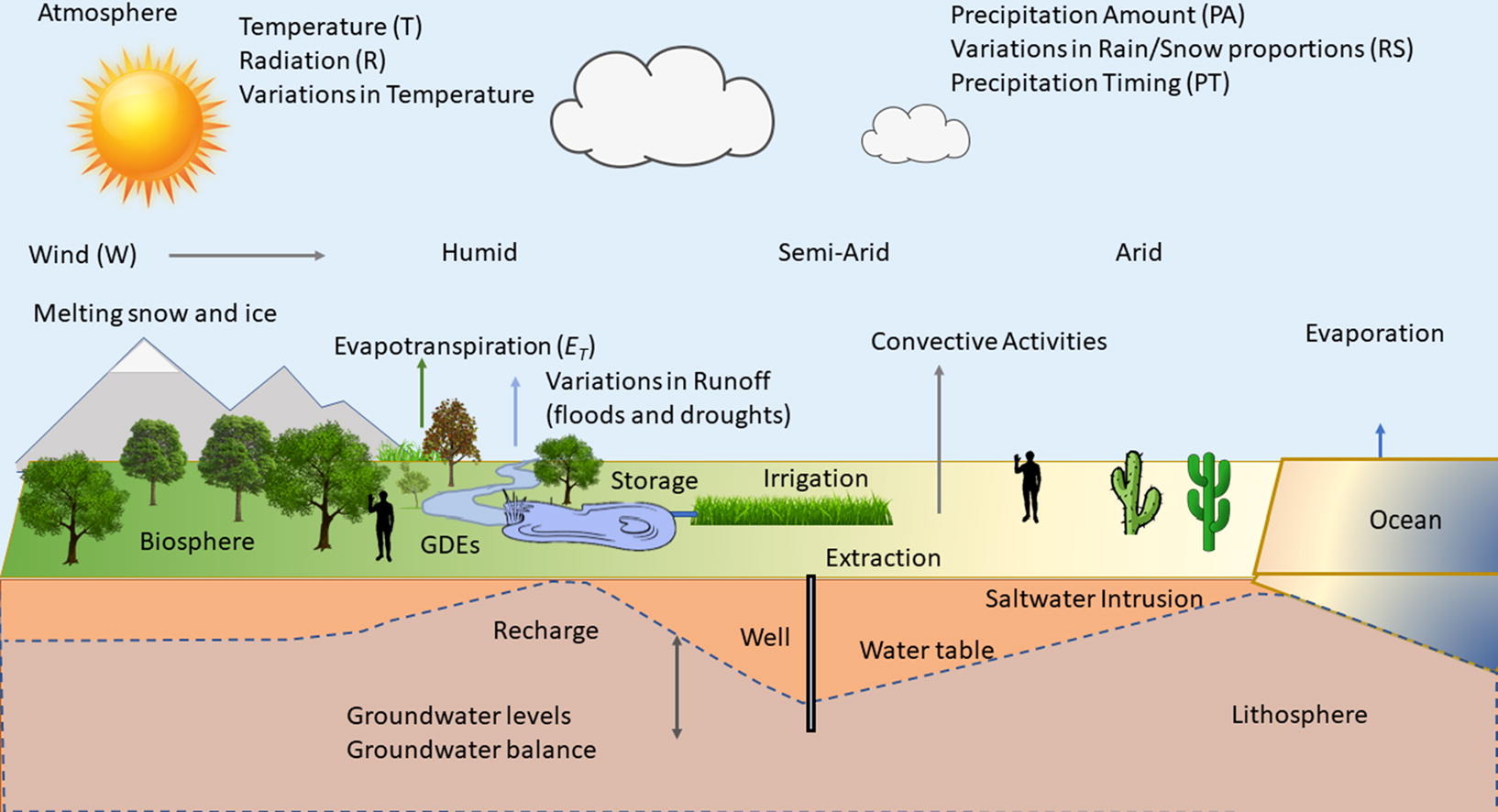

Amobi has used the insight he’s gained in these courses to publish Groundwater System and Climate Change: Present Status and Future Considerations in the Journal of Hydrology.

Amobi has also returned to teaching. He has taught GEA1000 Geography for a Changing World, GEO2200L Physical Geography Lab, and GEO2242 Extreme Weather.

Amobi also reviews papers for the Journal of Hydrology – where he received a Certificate of outstanding contribution in reviewing.

Of course, Amobi doesn’t just take courses in two different degree programs, teach courses, serve on a department committee, and work with academic journals – he’s also a working scientist. While the global pandemic has reduced the ability of the Mossa Lab to go into the field, Amobi has made many data collection trips to the Apalachicola River.

Amobi and his colleagues gather hydrologic data and bathymetric data using a boat based sonar system to assess the topography of the river bed and its geomorphology. They then fly drones to map out the whole river profile which allows them to build up a model of the topography and connectivity of the river. By comparing these detailed topographic and geomorphological models to historic bathymetric data collected by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), they are determining the exact impacts of the Jim Woodruff Lock and Ddam on the floodplain surrounding the Apalachicola.

Since the Jim Woodruff Lock and dDam was built in 1954, it has provided economic benefit by improving navigation, providing water to surrounding cities, and generating hydropower. However, large engineered structures disrupt the natural flow of waterways, disrupting the entire river ecosystem and changing water flow rates and sediment deposition on the surrounding floodplain. This research is providing critical insight into how policy makers can develop better plans to release water to mimic a more natural flow. If managed correctly, the dam can continue to provide economic benefit, while minimally impacting the health of the larger ecosystem.

Amobi’s research has caught the attention of his fellow scientists here in the southwest. He has won two poster awards from the Florida Society of Geographers.

He was also featured as a Highlighted Student Member of the Southeastern Division of the American Association of Geographers (SEDAAG).

How has he been holding up during the pandemic?

Like everyone else, Amobi started baking once the pandemic forced everyone to stay home. After gaining more weight than he liked, he has stopped his experiments in baking and is working on keeping himself fit and healthy.

While it’s been hard to be isolated from the outside world, Amobi has thrown himself into his scholarship – studying, taking notes, and preparing for the courses that he teaches.

Follow Amobi on Twitter

Credit: Mike Ryan Simonovich