Dr. Katy Serafin

Pronouns: she/her

Assistant Professor of Geography

Affiliate Faculty, Florida Climate Institute

Affiliate Faculty, UF Water Institute

University of Florida

Focus Areas:

Research Statement: I am a coastal scientist who researches extreme sea levels and coastal hazards to better understand how our coastlines are changing and the resultant consequences for people and places. I combine observational datasets with statistical and numerical models to understand the frequency, drivers, and impacts of coastal flooding and erosion events. Some of my interests include compound flooding hazards, extreme value analysis, coastal processes, human-natural coupled systems, flood risk management in a changing climate, and climate change adaptation and resilience. The dynamic and broad nature of coastal science demands a highly interdisciplinary approach and I work with collaborators in different fields, institutions, and government agencies to enhance the resilience of communities to the impacts of coastal hazards.

Who is she?

Dr. Katy Serafin is an Assistant Professor in the Geography Department. She is a coastal geoscientist who conducts research on coastal flooding and extreme events. She’s particularly interested in compound flooding – where high tides, storm surges, and river runoff intersect – and how flood risk management can transfer risk to disadvantaged communities. Katy is also affiliated with the Florida Climate Institute and the UF Water Institute. Prior to her current position, Katy was a Postdoctoral Researcher at Stanford University. Katy grew up in New York about an hour north of New York City and spent most of her summers on the beaches of Maine and North Carolina’s Outer Banks, where she cultivated a deep appreciation of coastal landscapes.

How did she get here?

Growing up in New York State, Katy had lots of opportunities to get to the beach as a kid. With English teachers for parents, Katy and her siblings had the freedom to travel during the summers, visiting her mom’s family in coastal Maine and their family’s summer house on the Outer Banks – a line of skinny barrier islands just off North Carolina’s mainland. Katy spent her childhood on, in, and surrounded by water. While vacationing on the beach, the family would pass the days swimming, fishing, and boogie boarding.

There are certain aspects of the coastline, especially in Maine, that Katy enjoyed but didn’t fully understand until she was studying science. As a kid, she was fascinated by a big, barnacle covered pile of boulders her family called The Rocks. She initially assumed they were a natural feature, but later learned that the rocks were a jetty, an engineered structure designed to control inlet migration and minimize sediment accumulation within the inlet.

Katy aspired to be a teacher, like her parents. She had always loved science, but her plan to become a science teacher didn’t solidify until late in High School, when Hurricane Isabel (2003) made landfall near their beach house and tore through North Carolina, causing millions of dollars of damage. The storm carved an inlet through the island, leaving the town of Hatteras inaccessible by car until the Army Corps of Engineers were able to fill the inlet and rebuild the road. While the family didn’t want to see their second home damaged, Katy was concerned for the residents who lived on the island full time. Now she finds it hard to look at a place without thinking of the infrastructure that’s in place and the lives of people who are impacted by coastal hazards.

When Katy started at Connecticut College, she was a Physics major in a 5 year degree program that would culminate in her graduating as a credentialed science teacher. She took an undergrad course on coastlines, where she discovered that one could formally study hazards and make a career studying coastlines. She quickly switched her major to Environmental Studies, the home of Geography, Ecology, and Geology at Connecticut College.

Katy’s adviser encouraged her to do an Honors Thesis evaluating coastal change on two beaches along the Long Island Sound and suggested she look into attending graduate school where she could merge her interests in teaching and research. She was able to secure an internship that let her spend a summer working with the United States Geological Survey’s (USGS) Coastal and Marine Science Center in St. Petersburg, Florida. At the USGS, Katy worked on a project analyzing coastal change on Fire Island, New York.

Upon completing her bachelor’s degree, Katy returned to Florida and took up a full time position as a Data Analyst at the USGS. She joined researchers investigating the coastal impacts of extreme storms and hurricanes by combining airborne Light and Detection Ranging (LIDAR) and aerial photography surveys to study sandy beaches from Texas’ Gulf Coast to Long Island, New York. Katy was responsible for characterizing the shape of dunes pre and post storm and assessing how they changed due to high water during hurricanes. Shortly after starting the job, she was able to work on analyzing Hurricane Ike – a Category 2 storm as big as the Gulf of Mexico whose storm surge devastated the Bolivar peninsula.

Katy had always considered her time at USGS as a temporary break before grad school – while there she understood that she wouldn’t be able to drive her own research without more education. After a few years with the USGS, she joined the Oceanography program in the College of Earth, Ocean, and Atmospheric Sciences at Oregon State University, where she earned her Master’s and PhD.

In the Pacific Northwest, there aren’t hurricanes but instead are large extratropical storms that come off the Gulf of Alaska and drive completely different coastal conditions. Katy enjoyed studying an entirely different system from the Atlantic and the Gulf coasts.

There have only been systematic coastal measurements of waves and sea levels in the Pacific Northwest and across the world for 30-50 years. While some of the oldest consistent measurements begin in the late 1800’s, there are very few records from more than 100 years ago. While 30-50 years may seem like a lot of data, we may not have experienced or recorded rare, large events. During her time at OSU, Katy explored the combination of factors which drive extreme coastal water levels, like tides, storm surge, and waves. She developed a statistical model that combines waves, tides, seasonality, and storm surge processes which may have not occurred in our short records, but are capable of co-occurring to assess what extreme coastal water levels might look like in different scenarios. “We had a particular combination of conditions in the last 30 years, but under another set of variables coastal water levels might look very different.” She also incorporated coastal river flow into the model, accounting for further complexity found in many coastal cities and towns. She asked “How do the combinations of tides, storm surges, and river flow influence flooding?” and the answer was compound flooding events.

Katy wasn’t just building models in the lab, she also gathered data in the field, which further informed her statistical models. Her lab group evaluated coastal change by surveying the elevation of the beach along transects across beaches in Oregon and Washington. During low tide, someone would walk with a backpack equipped with real-time kinematic GPS (RTK-GPS) from the dunes out into the water. During high tide, others would go out on jet skis equipped with echo sounders and RTK-GPS to measure the depth from approximately 1 mile offshore to where the waves break. This would provide a complete transect of the beach from the dunes out to deep water to compare change from year to year. In addition to her research on jet skis, Katy started rowing on the Willamette River with the Corvallis Rowing Club and picking up the occasional basketball game when she could.

Upon completing her doctorate, Katy moved to the department of Geophysics at Stanford University as a Postdoctoral Researcher. At Stanford, she continued her compound flooding events research, exploring how changes to the climate and built environment alter the likelihood of flooding and influence community resilience.

Katy dove into community driven work exploring how flood impacts can be influenced by physical infrastructure. The human impact of natural flooding after Hurricane Irma and the coastal jetties of her youth came together as she explored downstream consequences of engineering structures in San Francisquito Creek in Palo Alto, California. Traditionally the questions of flood event damage are based on the replacement cost of infrastructure and are asset driven. Disadvantaged communities have low value assets, but it still matters when they’re damaged.

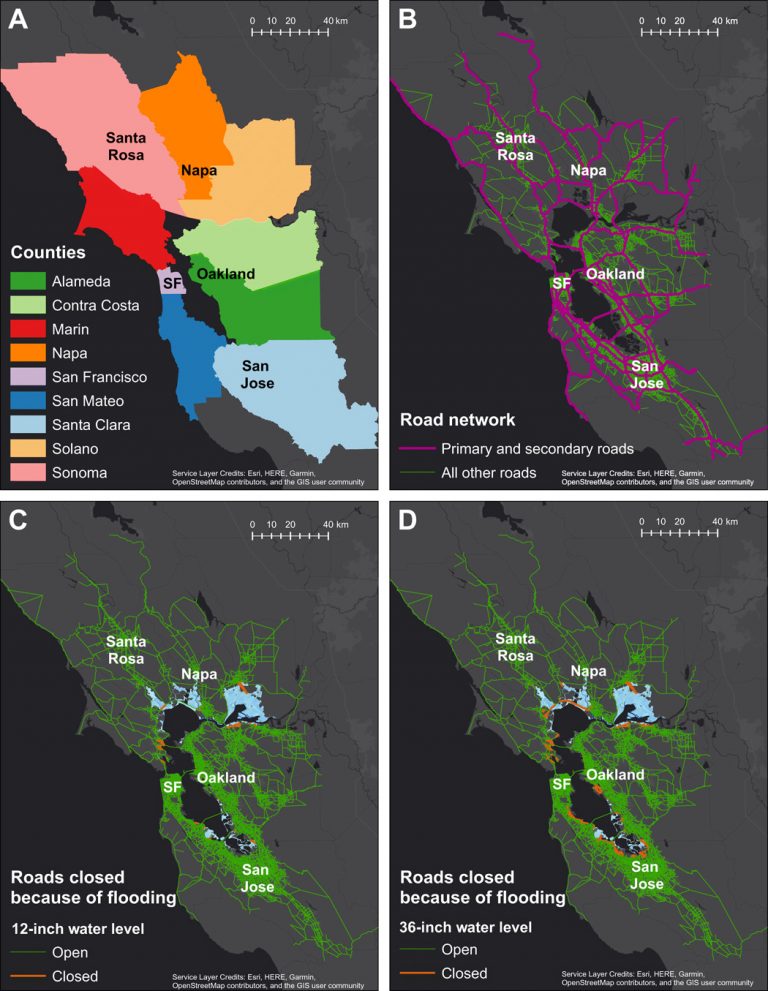

In her recent paper When floods hit the road: Resilience to flood-related traffic disruption in the San Francisco Bay Area and beyond, published in Science Advances, Katy shows that communities with sparse road networks are disproportionately impacted by flooding events, even if they are physically distant from the actual flooded land. People whose neighborhoods are flooded can be stuck at home, but communities up to 40 miles away may see their commute times increase. Road network density can be a better determinant of flood-induced commute delay than actual flood exposure. “By only looking at coastal flood exposure and property damage we could be missing a large part of the picture about how sea level rise will impact communities near coastal locations,” says Serafin.

Image courtesy: Science Advances.

In the San Francisco Bay Area, Katy explored the Bay and sloughs while rowing with the Bair Island Aquatic Center.

What’s she been doing at UF?

Katy moved to Gainesville in December 2019. While settling in and reacquainting herself with a Florida lifestyle, she’s been developing a series of classes for the Geography Department focused on sea level rise, extreme event analysis, and coastal hazards.

- Coming soon: Quest2 course IDS2935 Living with Rising Seas

- Coming soon: GEO3930 ST:Sea Level Variability and Change

Katy has also been adapting her work to the local environment by beginning to evaluate how the duration of nuisance flooding (also referred to as “sunny-day” or “high-tide” flooding) have been changing here in Florida and across the United States using tide gauge data. These low level flooding events have the potential to disrupt daily routines and put added strain on infrastructure systems. Sea level rise has increased nuisance flooding – how long an event persists above a flooding threshold may dictate the severity of disruption and impacts. Places that flood less frequently but for a longer time may be impacted more than places that are regularly flooded, but drain quickly. Katy is working on characterizing the physical nature of these events and will work towards understanding their impacts beyond just property damage.

How has she been holding up during the pandemic?

Having moved to Gainesville in December, and traveling extensively in February and March, Katy didn’t get much of a chance to explore Gainesville before going into lockdown.

While unable to check out Gainesville’s downtown restaurant scene, Katy and her husband have been experimenting with lots of new recipes, including some exciting Indian curries. They’ve also been socially distancing from the local megafauna while taking walks at Sweetwater Wetlands Park.

Katy has been getting crafty, cutting the tops of wine bottles and making her own candles at home.

Since she hasn’t yet been able to meet local rowers, she’s been taking part in the GeoGator Workouts (contact Dr. Jane Southworth for details).

Most importantly, Katy has made a home for Percy and Olive, her new kittens.

Credit: Mike Ryan Simonovich