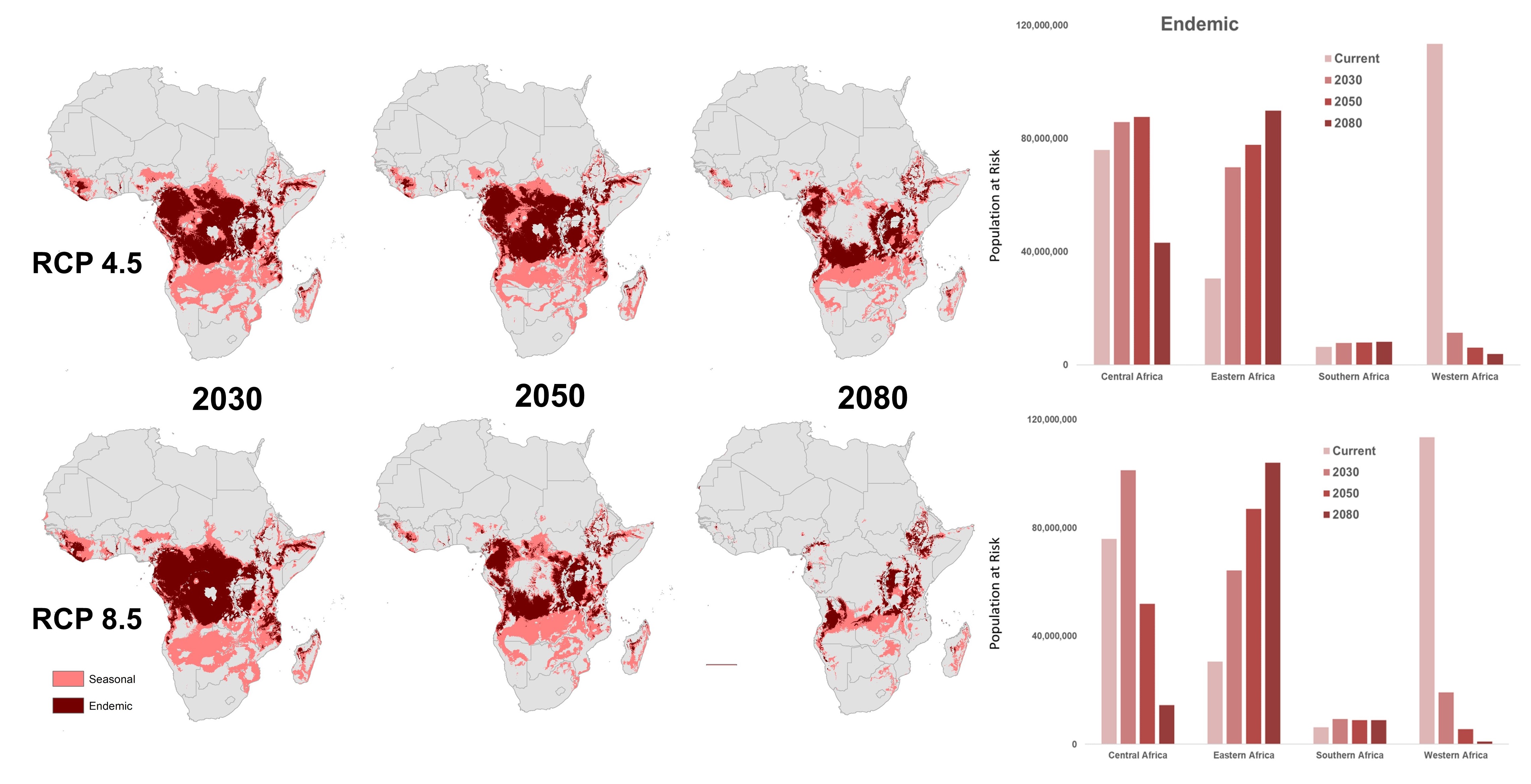

GAINESVILLE, FL – In a new paper in Malaria Journal “Shifting transmission risk for malaria in Africa with climate change: a framework for planning and intervention”, part of a cross-journal collection on the Contribution of Climate Change to Spread of Infectious Disease, QDEC’s Sadie J. Ryan, along with Cat A. Lippi and collaborator Fernanda Zermoglio (M.S. UF Geography ‘00) show how projected climate change will alter malaria transmission potential patterns, placing populations at risk in different parts of Africa in 2030, 2050, and 2080, under different emissions scenarios. Funded by the USAID ATLAS (Adaptation, Thought, Leadership, and Assessments) project, this study aimed to describe how regional changes in risk would affect different places and populations in different ways, relevant to decision making for intervention.

Malaria interventions for seasonal outbreaks differ from managing year-round risk, so understanding where these patterns will change is important for both anticipating new regions at risk, and where to change health infrastructure and capacity. In Western Africa, there is a massive drop in the number of people at risk of year-round malaria transmission, but this is a function of increasing temperatures, putting much of the region at hotter temperatures than the mosquitoes best transmit. The region expecting the greatest risk increase by 2080, in terms of people, is the densely populated Eastern Africa, where seasonal risk will increase and push into novel areas, according to predictions.

This regional approach to thinking about where malaria transmission will change is important to global health policy. “It’s hard to communicate the intersection of demography and geographic risk, so aligning our scales with those at which decisions are often made is useful” Dr Ryan points out. Mapping disease risk is not enough, she continued, because we make decisions based on how many people, and when, not just where.

Read the whole paper at Malaria Journal.